History of Chadds Ford

The land around Chadds Ford was inhabited by the Lenni Lenape Indians centuries before the Europeans arrived. In 1638, the first European explorers, the Swedes, discovered the Brandywine and by 1700, English Quakers made up most of the population in the area.

In 1707 "Ye Great Road to Nottingham," now U.S. Route 1, was laid out from Baltimore to Chester. It was one of the five main routes from Philadelphia in the early 18th century.

During the late 1730's and 1740's when John Chads operated a ferry service across the Brandywine, the crossing place became known as "Chadds Ford." About 1827, a bridge to span the river was built.

On September 11, 1777, Continental troops formed a line of defense along the eastern bank of the Brandywine. George Washington had chosen this spot to halt the British advance toward Philadelphia. General William Howe split his forces to outflank the Continental army in the Battle of the Brandywine.

After a day of fierce fighting, the Americans retreated to Chester and the British camped on the battlefield for five days, ransacking nearby homes.

During the 1800, the harnessing of waterpower for use in mill operations was a major factor in the growth of the area. The mills not only manufactured goods such as gunpowder and paper, they also processed grain and timber grown in the area.

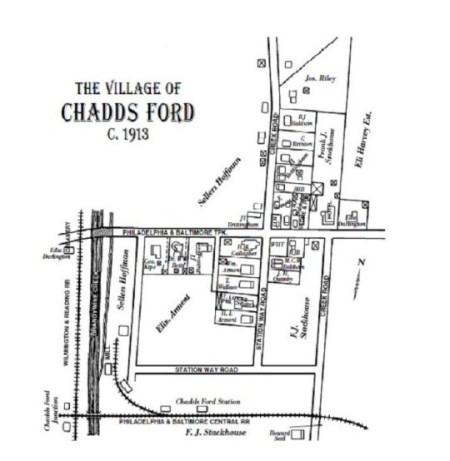

In the late 1850, the railroad came to town. Two lines came to Chadds Ford: the East-West running Philadelphia and Baltimore Central RR in 1858 and the North-South running Wilmington and Reading RR a few years later. The two lines met at Chadds Ford Junction, while only a few hundred yards away on the East side of the Brandywine was the Chadds Ford Station.

The railroads played a significant role in the economic growth of the area. Spurs were laid out to accommodate the Kaolin companies where fine white potter's clay was mined at the turn of the century. The railroad also brought city people from Wilmington and Philadelphia who discovered the lush rolling hills of the Brandywine Valley. To have a summerhouse in Chadds Ford became very fashionable.

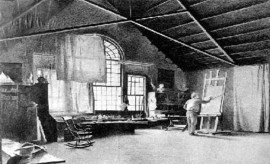

During this time, Howard Pyle held summer classes in Chadds Ford that attracted students from all over the country including Frank Schoonover, and Violet Oakley. One of his students was the young N.C. Wyeth from Massachusetts, who came to study under Pyle and decided to settle in Chadds Ford. Pyle's studio and its students gave rise to the celebrated Brandywine School of Art, fostered by three generations of the Wyeth family.

In the early 20th century, the village of Chadds Ford was still a quiet crossroads surrounded by acres of farmland. After WWII, better roads and the population explosion of the 1950's brought people from the cities to countryside transforming the rural landscape into a burgeoning suburban community.

Following is a note about Chadds Ford written by James Duff, Executive Director Emeritus, Brandwyine Conservancy and Brandywine River Museum. This was originally written at the request of and published by The Kennett Paper, 1999. Revised 2015

Historically, Chadds Ford is the village and surrounding land on both sides of the Brandywine River where Route 1 (aka Baltimore Pike, aka the Great Road to Nottingham) crosses the stream. No doubt, at different times the request for a definition of the community would have received very different answers because of changing political boundaries and postal districts. Until the late 18th century, all of Chadds Ford was in Chester County, but the division of the county to create Delaware County made a definition more difficult. Moreover, roads built and roads abandoned have greatly changed the appearance of the place, as a have buildings constructed and demolished. Nonetheless, one hundread years ago and even fifty years ago, everyone in the region knew what was Chadds Ford and what was not. Now, with a large area served by Chadds Ford post office and the former Birmingham Township name changed to Chadds Ford Township in Delaware County, the issue has grown more confused. People miles from what is commonly referred to as the "village of Chadds Ford" say that they live in the community and, because of tradition, have a just claim. On the other hand, people no more than a mile and a half from the village have claimed other addresses. Perhaps because of the confusion, which is often sensed by visitors, for decades it has been common among authors around the world to describe Chadds Ford, not geographically or politically, but in terms of its landscape and its rich history of agriculture, a famous battle, milling industry, road and rail transportation, and extraordinary art. Because of all these circumstances, it seems sure that this celebrated place exists very much as a state of mind and that requests for a brief difinition of the community cannot be met. A good portion of Chadds Ford's unique romance derives from the difficulty of saying precisely what and where it is.